Robert Israel is a musician and composer, who, according to Peter Bogdanovich, understands silent films. It’s no ordinary phrase – this is obvious to anyone who witnessed him accompany any silent film. The energy emanating from him, when he sits behind a piano is thrilling. Just listening to him talk about silent films shows his burning passion towards the silver screen and its stars. It’s not everyday when you meet someone so enthusiastic about the silent films and who knows them so well. This year at Summer Film School Robert will accompany two silent classics, Now We’re in the Air by Frank R. Strayer and Wings by William A. Wellman (both 1927).

Your whole career is closely connected with silent films, you are not only a performer and composer, but also as a lecturer. What brought you to silent films in the first place?

My father had been born in 1915 and grew up watching “silent” films first run. Imagine being able to see a new release starring Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, or Lon Chaney! When Public TV would air these “silent” films in Los Angeles, my father would tell our family about it and we would watch and enjoy them together. I had dreamed about going to film-making school from when I was 13 years old, and at about the same time, I started collecting “silent” film classics. As I was aware that music was a necessary part of enjoying these subjects, I started to build a music library with my tape recorder using the aforementioned silent film airings on TV as my source–I did not play any musical instruments. Often, the music was by pianist/composer William Perry, or by the legendary organist, Gaylord Carter, who ultimately became a very dear and close friend of mine. By pure happenstance, I accidentally discovered that I had a natural love for classical music. The music of Franz Liszt became a profound passion of mine as well as the music composed by Scott Joplin. My fate was sealed–I chose to study music instead of film to become a pianist.

What is your approach towards the composing of music for silent films? Do you prefer to study the original scores intended for the film premiere? Is the historical accuracy to the original intention important for you?

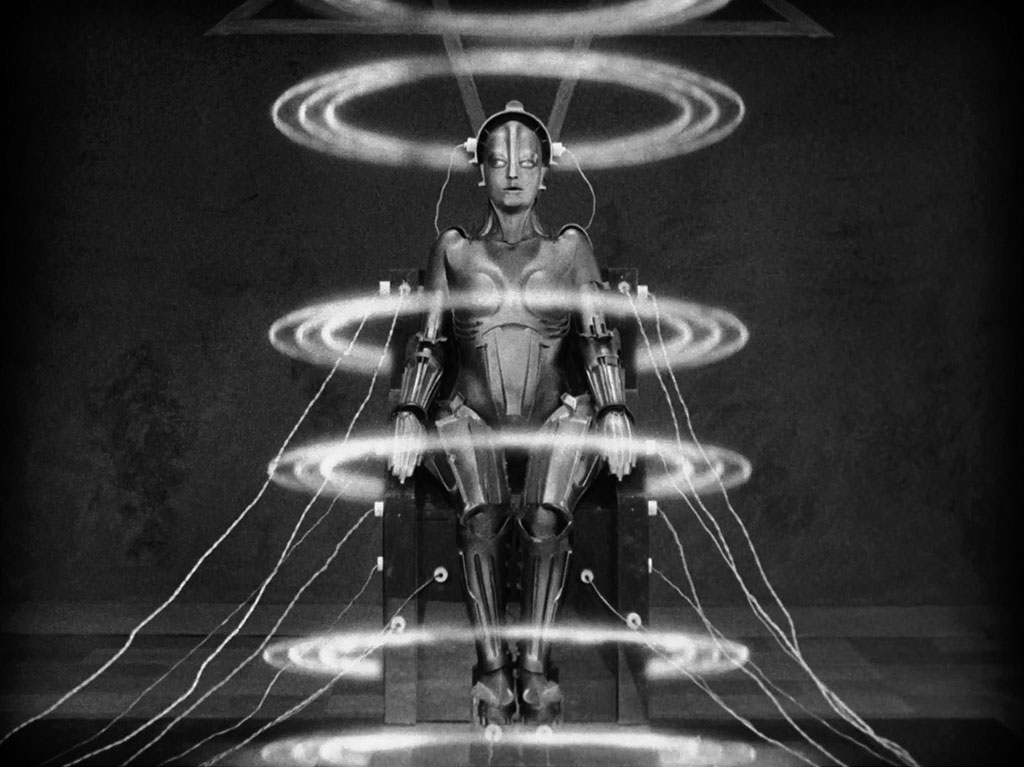

Performance practices of the time are of significant importance, but they are not the final word on how one may approach scoring a pre-sound era film. Just because something was created for a specific film in the 1920s does not mean that it is a suitable score. Historically, its place is secured, but that alone does not make it a worthwhile item to resurrect. As an example, Louis F. Gottschalk’s “original” score for the Douglas Fairbanks classic The Three Musketeers (1921) is one of the most disappointing original scores I have ever heard. Its failings to successfully employ effective music scoring provide numerous examples of how even the most splendid film production can be toppled with inappropriate music scoring material. On the other hand, his score for D.W. Griffith’s Broken Blossoms (1919) is a very sensitive and beautifully arranged work and serves the film incredibly well. There is a lot to be learned from studying period scores and the music of the time. Gottfried Huppertz’s score for Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) is a brilliant and astonishing score that demonstrates something of the advanced level of film and music presentations from the 1920s–one will discover many classic scoring techniques, foremost among them is the use of motivic material to further define characters, their motivations, and even help to define psychological themes. What is important to me is to serve the film musically, in such a way, that the mood and visions offered by the film can be supported and brought to life with the goal that the audience may become deeply involved with the viewing experience.

As the film language changed over the time, many people have problem now to watch the silent films and understand them the same way as the audience did hundred years ago. Do you work with that in your music and try to bring the silent films closer to the modern viewers?

The technology that prevails in the world today is vastly and dramatically different from one hundred years ago, but that is all that it is–a difference. True, “silent” films have a very specific language to them–the way they were shot, the style of acting, and the editing, but film is film is film. Some people truly do not have a taste for watching films in black and white, let alone films without sound, but if you show a short comedy to a group of children, usually they are all laughing and absorbing the entertainment value in a completely organic fashion–most will not even comment about the absence of color or sound. The reason for this is that children are very open minded, and if we as adults can approach “silent” films being as equally receptive, then we have a greater chance at the success of discovering the beauty of these films. With any form of art, particularly those created from decades long ago, it requires some study or background to help that art form become more accessible. Peter Bogdanovich said, “There are no ‘old’ movies really–only movies you have already seen and ones you haven’t.” Styles and social mores are always in a state of change, but people have changed very little over these many centuries. The love story and the tragedy of Tristan and Iseult remains one of the most relevant and revealing texts about love between two people. Are we to imagine that because it comes from the 12th Century that we cannot understand it?

When I am composing a score for a “silent” film, my focus is upon understanding the entire meaning and structure of the film. Often I find myself spending endless hours doing research on the time period and the setting of the film’s story, and learning about the film’s production history as this can be revealing about how to approach the scoring question. Buster Keaton’s magnum opus, The General (1926), takes place during the American Civil War in the 1860s. Many of the war songs composed at the time are still very well known in America to this day. One may argue that an audience member in Brazil will be ignorant of such music and will not miss it if it is not a part of the contemporary presentation; but, if that same audience is watching Gone with the Wind (1939), which features the very same Civil War tunes because of their historical accuracy and authenticity, how do we argue that because Gone with the Wind was produced as a sound film in 1939, and that because The General was produced without sound in 1926, that similar accuracy and authenticity is less important for the Keaton feature because it is a silent film? There is no law against leaving out these melodies, but from my point of view, regardless of where a film was made (America, Japan, France, Russia, Germany), the cultural and historical context must be a part of the consideration of the scoring process–this, in turn, often adds to the accessibility and allowing a contemporary audience to get as much out of the film presentation as is possible.

What are the specifics of composing music for silent films now?

That all depends upon the context and basis of the “silent” film being presented. Will it be a presentation in a theater, or for a Blu-Ray release, or for television? Budget will also be one of the most influential factors. As these films are hardly at the high end of commercial value, opportunities for orchestra scores become more and more rare, which is lamentable because the higher the level of musical treatment these classics are given, the greater chance they have of reaching a broader audience and being received with positive enthusiasm.

With your music do you follow actions and events on the screen, or rather focusing on the mood, the atmosphere and emotions the scenes evoke?

This really depends on the film’s genre–it is always important to treat all film carefully, thoughtfully, and to have a particular understanding of the subject matter. If one were to consider scoring Buster Keaton’s The General, and then also prepare a score for his film Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928), one is faced with the challenge of recognizing the disparate nature of these films: one is a dramatic comedy set during the American Civil War, and the other is classic comedy feature (with dramatic overtones) set in contemporary 1928. The storylines are completely different in spite of the fact that both are set in the Southern states of America, thus it is contingent upon a composer how to evoke a sense of the unique locales in both films, differently. Even the pacing of the comedy sequences is vastly different from one another–much of the action in The General takes place on moving trains, whereas in Steamboat Bill, Jr., the action takes place near a river, or on steamboats, or in the midst of a violent cyclone. The formidable challenge for scoring The General is discovering how to capture the rhythmic action (which is practically pulsating at a nonstop ‘allegro’ once the chase begins) and finding variations in style and tempo to keep the music from becoming monotonous. Steamboat Bill, Jr., has different challenges in that this is one of Keaton’s most emotionally expressive films. Both films contain emotion, no doubt, but the prominent action in the two features is quite varied. The short answer to your question is, yes, I follow the actions, events, the mood, the atmosphere, and the emotions evoked by any film I am scoring.

Do you write the whole composition note by note, or how much improvisation is involved?

When I am preparing an orchestra score, it is preferable to have the entire score worked out carefully and synchronized with the feature subject. There is still plenty of room for a spontaneous performance from the orchestra if one is conducting in a spontaneous fashion. Even with the most careful planning and rehearsals, live performance presents many opportunities for things that can go right AND things that can go wrong. It is also possible to prepare an orchestra score in which there are specific opportunities for an instrumentalist to be given an ad lib cadenza, something where they would be required to improvise, but this is very high risk as not all musicians enjoy improvising. You must have specific players in mind to do something like that. If I am performing as a soloist, I still prefer to carefully prepare a score as I believe that a film is best served with as much preparation as is possible. Most of my formative years performing were spent improvising for films I had never seen before, and although this can be fun for both the artist and the audience, if a film calls for a specific piece of music, and you do not know that composition, then it can become a potentially embarrassing situation, particularly when an audience member knows it and asks you after the performance, “Why didn’t you play the song that was in the film?” The artist may be able to say, “This is the very first time I have seen the film, so if I had had the chance for a preview, I could have had that music ready.” The artist has a solid answer in their defense, but the end result is that the audience member is still going to have the memory of the missing music that they were expecting to hear, and the performer that had failed to deliver upon that expectation.

You are not only performer, but also composer, creating scores for the whole orchestra. Which approach is closer to you? To conduct the whole orchestra, or rather perform on your own and have control literally in your hands?

It is far more manageable to play a solo piano score as it allows me the freedom to change my mind about something in the score at a moment’s notice, or to improvise should a moment call for it, but conducting an orchestra, for me, is simply using a far more complex musical instrument to create the music sounds. Depending upon the context of a presentation, my personal preference would be to have an orchestra for every show in which I am providing a music score, but the practicalities of touring with an orchestra, let alone mounting an orchestra presentation, can be both formidable and prohibitive. Cost and budget are serious considerations, but if we look back to the 1920s, it was the top quality movie palaces which offered orchestra as their preferred musical component, not piano. For that matter, although the theater pipe organ was also a prominent instrument in the movie houses, orchestras got the limelight and the highest level of treatment–the organ would serve to play music for the smaller attended shows during the day, or very late at night, but of course, organ could also be featured during an orchestra presentation as part of the orchestra.

What about different cultural approaches towards silent film? Do you also draw inspiration elsewhere, such as the Japanese Benshi tradition for example?

Many years ago I did a program with the Japanese actor Mako. He was a brilliant performer based in Los Angeles, and with the addition of a percussionist, and I playing theater organ, we did a presentation of Sessue Hayakawa’s film The Dragon Painter (1922) as a blend of the Japanese Benshi tradition and a Western traditional silent film musical scoring. The film print had French intertitles, so Mako beautifully performed the English language translation. As he was a highly gifted actor, his performance was not just a mere reading of intertitles, but was delivered with the subtle and precise technique of the most polished theater performer. On another occasion, I performed music for Prof. Erikki Huhtamo (from Finland, but is a professor at UCLA in Los Angeles) who was presenting a Magic Lantern program. He composed a story for his magic lantern slides and gave a performance of that story with me providing piano music. For that, I approached the material as I would a silent feature, but I also used a wide variety of natural sounds, the idea of which was inspired by my days as a composer for contemporary documentary film for television back in the 1990s. For other various silent film presentations, particularly those with an abstract or avant-garde feeling, I am more inclined to experiment with the style of music to provide a suitable score.

In terms of various genres, what is your opinion on rock or electronic music with silent films? There is even disco soundtrack for re-cutted version of Metropolis by Giorgio Moroder…

I believe that the context of a screening has some impact on my feelings about silent films presented with traditional style music, and those featuring rock, or pop-electronic music. There are a handful of successful groups that provide contemporary pop music accompaniments, and often their shows are billed where they are the main attraction, the film being featured in their programs. Personally, I am more partial to traditional scoring techniques, but I believe that a viewer is more likely to get far more out of a silent film viewing experience if the film is screened with an appropriate score, and this is possible with a pop-contemporary approach, but too often are there example which I think demonstrate one of the issues with contemporary scoring methods. Michael Nyman is a well known and incredibly successful composer. He has had a vast experience in scoring modern day film and possesses a long list of impressive credits. His score, however, for Dziga Vertov’s A Sixth Part of the World (1926), gives me the impression that he was more focused on his compositions than on scoring the film subject. He even went on to say, when his score was being presented with the Vertov film in Moscow in 2011, that, “I’m sure that contemporary Russians will find this film quaint and totally incomprehensible.” Perhaps this indicates the reason his score seems in competition with the film rather than providing its voice. Hieroglyphs at one time were thought to be incomprehensible until someone opened the door to understanding their meaning–art is not so different in this respect in that we must do some research to understand more about the times in which an artist work was created, and even more so about the artist himself, in order to gain a deeper understanding of the artwork in question. My point is that even with a highly skilled composer, the visual film language and fundamental basis of the communication of ideas is a profound contrast with sound cinema. One cannot merely expect to slap some kind of music background onto a silent film and expect to reveal much of anything in the film unless it is by pure happenstance; hence, why I feel research and careful preparation are necessary when approaching the subject of scoring a silent film. Pop-modern scores and silent films from the 1920s are inherently anachronistic when paired together; thus, it requires very careful preparation to make that quality less focal so that both the music and film are blended together in such a way as to achieve a result that feels convincing and natural. It is for a similar reason why great paintings are given specially chosen frames to finish off the presentation of the painting–the frame is not just a perfunctory border surrounding the piece, but helps to finish the presentation and support its contents.

Peter Bogdanovich said about you: “Robert Israel understands silent pictures. He doesn’t overwhelm them.” So what are the right elements of a good musical accompaniment?

Believe it or not, this is an extremely difficult question to answer. It feels similar to the question of what makes a symphony a good composition? Or, what makes this specific recording by Eric Clapton better than some of his others? Or, what makes a sculpture a good one? The score to Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights (1931) is about as perfect a silent film score as one will ever hear. It is unique in that Chaplin also composed this music, not in the traditional sense as he was not with the ability to notate and orchestrate complex material, but working with Arthur Johnston and Alfred Newman, Chaplin was able to dictate very specific instructions to the musicians, including the specific instruments he wanted to have play certain melodies at various times. The end result is a highly polished score which is an integral part of the film. Compare that with Chaplin’s very own score for his dramatic feature A Woman of Paris (1923), which he created very late in his life (it was released in 1976) with very different musicians, the results are nothing compared with his earlier work. My point in bringing this up is not to criticize the 1976 score, but to point out that the success of the City Lights score is not because it was done by Chaplin, but rather that Chaplin’s genius was more fully realized with his inspired scoring, and that film gave him countless opportunities to exploit those same scoring techniques–Chaplin truly did not miss a beat. The score is witty, it is vibrant, it is filled with beautiful melodies, it is very tender, and it is eloquent. The music score is filled with a variety of techniques, defining both the non-diegetic music to support the film, and the diegetic music on screen, which include: fully composed selections, recitatives, sound effects which are indispensable to the success of the comedic action, character themes, action music, musical jokes, and the end result being not only a fully intellectual approach to scoring, but a highly emotional experience of the most rewarding kind.

What is your most favourite silent film?

This really depends upon the film I am watching at the time you ask me this question. It is impossible to choose a single favorite and I refuse to try, but if you ask me what some of my favorites are, I would answer something like:

For comedy, Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights (1931), Buster Keaton’s The General (1926), Harold Lloyd’s Girl Shy (1924), and Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy’s Big Business (1929)–this being an utterly incomplete list.

For drama, Douglas Fairbanks’ The Thief of Bagdad (1924), Lon Chaney in The Unknown (1927), John Barrymore in The Beloved Rogue (1927), Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927), F.W. Murnau’s Faust (1926), Mauritz Stiller’s The Song of the Scarlet Flower (1919), Victor Sjöström’s The Outlaw and His Wife (1918), Vsevelod Pudovkin’s Mother (1925), Josef von Sternberg’s The Last Command (1928), Abel Gance’s La Roue (1923), and Ivan Mosjoukine in Kean, ou Desordre et genie (1924).

Looking upon these titles mentioned as some of my favorites, there are just too many other titles I have not even mentioned here, and that has me feeling just a little sad.